War & Ham: The Difference Between Children's and Adult Literature, or How to Get a Grip

As a beginning writer for younger readers I often wondered about the difference between children’s lit and adult lit. There are some obvious answers like the fact that kid lit is aimed at children and is appropriate for them, although marketed to adults. There is the possible presence of illustrations, and the use of simpler vocabulary and shorter sentences, although these differences disappear in young adult literature.

Adult Lit vs. Kid Lit: War and Peace vs. Green Eggs and Ham

Some say children’s literature is whatever children choose for themselves, including comic books and manga, and some stories written for adults (like THE ADVENTURES OF TOM SAWYER). Middle grade and young adult novels almost always have young protagonists, most often a year or two older than the age group they’re written for and the story is from their immediate or still-young point-of-view. Adult fiction can have child or teen protagonists but the story is almost always told from an adult POV looking back.

Fiction for younger readers may also have more of an emphasis on story--versus fancy footwork with prose. Any writing that calls attention to itself at the expense of keeping the young reader fully engaged in the fictional dream has a hard time justifying itself in a children’s novel. (The use of rhythmic, melodic, and alliterative language in picture books is a different matter entirely.) But complex emotional truths, profound moral quandries, pain ,and struggle are just as present in good children’s literature as in that for adults. Same goes for subtext. Last but not least, you’ll find humor in many of the most successful stories for young readers, regardless of subject matter.

We all could use a little more humor.

Novelist Orson Scott Card said, "one can make a good case for the idea that children are often the guardians of the truly great literature of the world, for in their love of story and unconcern for stylistic fads and literary tricks, children unerringly gravitate toward truth and power."*

Adult protagonists realize stuff and change, but in a good story for younger readers, the protagonist is almost guaranteed to follow an arc of transformative learning and GROWTH, figuring out who they are in relation to their families, peers, and communities along the way.

One of my wise teachers at Vermont College of Fine Arts, Tim Wynne-Jones, summed up the difference this way: “Children’s literature is about learning how to get a grip. Adult literature is about letting go.”

Getting a grip.

Kid Lit is concerned with how we make our way in the world: how to differentiate shapes and letters, survive scary incidents like a new sibling, a friend’s betrayal, being stranded in the wilderness, a dissolving family, sexual and gender questioning, drugs, even zombies--fantasy and the paranormal, of course, are just the real world in disguise. In other words, how to make sense of this difficult world and come of age to handle it on your own.

Then you can start learning to let go.

Most children’s writers remember learning to get a grip with great clarity and some fondness. Maybe this is why we are children’s writers. Many of us also struggled with it somewhere along the way. In addition to wanting to tell stories and entertain our young readers, we are pulled to share our experience and knowledge with them.

Didacticism in anything for younger readers falls flat faster than a dropped kickball by the way. But we cannot help and sometimes don’t even know until a work is completed, what is at the heart of the stories we tell. Our themes are generally optimistic: persevere; believe in yourself; do the right thing; make good choices; and that, as difficult as it is, the world is full of wonder and beauty.

In good children’s literature, the young protagonist solves the story problem themselves, probably for the first time. No adult should helicopter in to save the main character (good to remember as a parent, too). But of course, in reality, parents, teachers, and librarians help kids learn to get a grip, all day every day. I am and have always been grateful to the teachers and librarians who put THE WITCH OF BLACKBERRY POND, THE HIGH KING, and ISLAND OF THE BLUE DOLPHINS in my small hands, not to mention indulging my hunger for ghost story collections. They actively encouraged me to access the world of imagination to experience outstanding stories that lived and breathed and shook me profoundly. The books allowed me respite from the “real” world, while at the same time giving me the chance to safely experience it in action. Through reading, I did learn about truth and the rules of power. And I learned how to get a grip.

More or less.

* Card, Orson Scott (November 5, 2001). "Hogwarts". Uncle Orson Reviews Everything. Hatrack River Enterprises Inc.

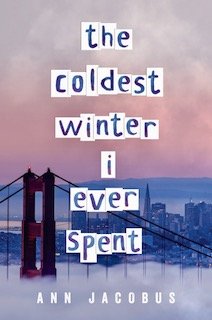

My latest YA novel: THE COLDEST WINTER I EVER SPENT. 18-year-old suicide prevention worker Delilah’s terminally ill aunt challenges Del’s ideas about life and death.

18-year-old suicide prevention worker Delilah’s terminally ill aunt challenges Del’s ideas about life and death